The Problem With Being Impressive.

I’m dangerously good at everything. That’s not the compliment I thought it was.

t’s the kind of line people mean as praise. And for most of my twenties, it worked that way. It got me in the room, earned me trust, unlocked autonomy. I was promoted early, flown in late, tapped for problems nobody else could fix, solved situations where the only real qualification was “figure it out.” I’ve built brands, overhauled systems, scaled teams, fixed the pitch deck the night before the meeting. I’ve stepped into almost every kind of gap you can imagine, and it’s worked. My brain moved fast, my execution was clean, and my name came up in every meeting where something needed to get done—right and fast.

That ability has been foundational to my career. And I’m not giving it up. But lately, I’ve been interested in a different kind of performance metric—not how quickly I can execute, but how precisely I can choose what’s worth executing in the first place.

Impressive is a useful opening posture. But it’s not the posture you hold if you want to do serious work.

The Phase of Being Impressive

By 27, I had the career most people spend a decade trying to construct: high-trust roles, multi-disciplinary scope, brand and ops experience, P&L responsibility, internal comms and external storytelling. I’ve launched brands, led teams, turned vague ideas into functioning systems, pulled entire campaigns into coherence. I’ve operated in high-trust environments, owned difficult outcomes, and built a reputation for being someone who delivers—without drama, without ego, without excuses. I’ve been the person people rely on when it actually matters. I made it look easy. That was the trap.

Because when you’re good at everything, you get asked to do everything. And eventually, what looks like excellence becomes a form of erosion.

But I also know this: I’m not even close to what I’m capable of.

Being impressive got me here. It earned me access, trust, and the kind of momentum most people don’t hit for another decade. But the more I’ve grown, the more I’ve realized that being exceptional at this level—chaos navigation, institutional memory, high-output problem-solving—is not the same as becoming indispensable at the next one.

What got me here will plateau if I let it. And I won’t.

The Risk of Being Overcapable

Here’s what no one tells you: the better you are at context-switching, the more likely you are to be deployed as glue. That sounds noble—until you realize glue doesn't scale.

In tech and startup environments, there's a premium on range. We valorize generalists. We fetishize adaptability. But when range isn’t paired with discernment, it becomes a liability. You end up spending your best cognitive bandwidth solving problems that exist because no one upstream asked better questions.

You become the answer to every fire drill. Not because you’re the best person for the problem—but because you’re the only person with the context, the speed, and the EQ to clean it up without making noise.

It’s competence as containment. It rewards polish over progress.

Eventually, that edge turns dull. You still move fast—but it’s toward the same types of problems, solved with slightly more polish and slightly less thrill. Range without a core starts to feel like intellectual slippage: you know more, but you feel less.

The Invisible Burn of Understimulation

This is where the conversation around burnout fails most high performers: it assumes we’re collapsing under pressure. But for many of us, the real danger is cognitive atrophy.

I wasn’t exhausted from long hours. I was exhausted from low demand.

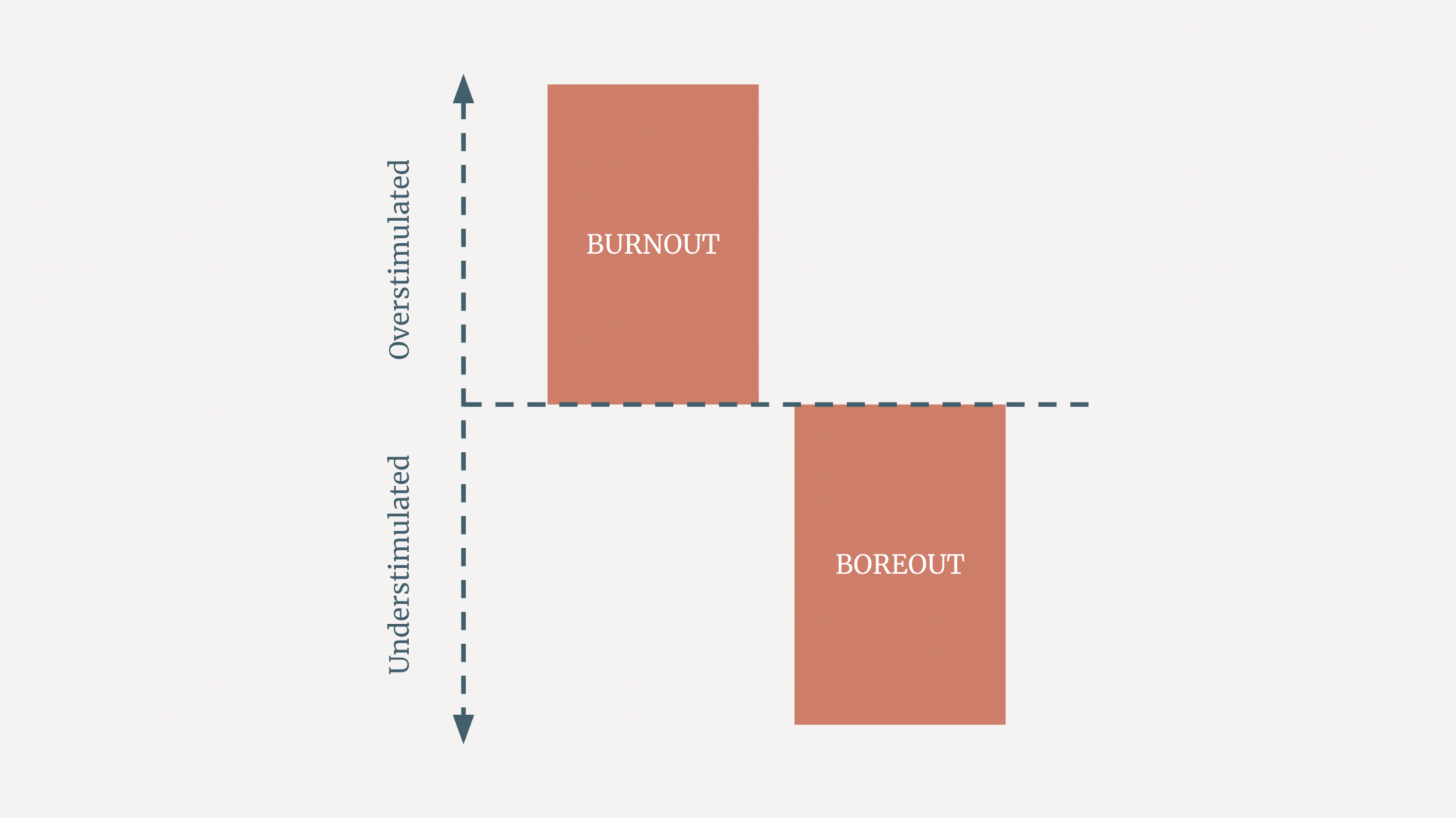

Research from Anne-Laure Le Cunff offers a more textured view of burnout, breaking it down into three categories: weariness, withdrawal, and worry. Most people assume burnout is about overload (weariness), but withdrawal—a quiet detachment from purpose, a sense of being intellectually underfed—is often what actually hollows out high performers. It’s called boreout.

It’s not that you’re drowning. It’s that you’re fading.

Psychologist Steve Savels describes boreout as the result of staying too long in your comfort zone. What looks like stability is actually stagnation. And what starts as a mismatch between skills and tasks eventually becomes a deeper erosion: a halt in personal development. You feel worthless not because you are underutilized, but because you are not challenged in a way that reaffirms your value.

That’s the twist. Boreout isn’t boredom—it’s existential drift.

And because it lacks the theater of burnout, it doesn’t register. You don’t crash. You just slowly stop innovating. You become so competent at too many things that the idea of mastery begins to feel indulgent. You stop pursuing depth because nobody expects it. Your range becomes your identity—and your prison.

Strategic Misalignment as an Operator’s Threat

Here’s where cognitive load theory cracks open something useful. Classically, effort is divided into three buckets:

Intrinsic load: the difficulty of the content

Extraneous load: friction caused by poor systems

Germane load: the mental work of structuring knowledge

But operators like me encounter a fourth: misapplied capacity—when deep capability is spent on shallow, misaligned, or excessively reactive tasks.

You’re still shipping. You’re still praised. But the cognitive elasticity that got you here? It stops expanding.

Instead of encountering novel constraints that push you into mental architecture, you start closing loops that don’t deserve you. You get sharper at tactical problem-solving and slower at asking better questions. You lose your ability to sit in abstraction, to structure unknowns, to endure ambiguity long enough to birth a truly original solution.

And because you’re still being rewarded, you don’t notice what you’re losing: range is expanding while depth is contracting.

It took me longer than I’d like to notice this in myself. That my fatigue wasn’t from overwork. It was from strategic misalignment—between what I could do and what I should be doing. I wasn’t under-resourced. I was intellectually misplaced.

This is how the careers of brilliant people calcify. Not because they aren’t capable—but because their environments only value their ability to perform, not their potential to direct.

Why I’m Rebuilding the Architecture

So I started engineering stimulation. Not as a bandage, but as a blueprint.

I’m treating my brain like a high-performance engine: complex inputs, specific fuel, regulated stress. That means:

Academia-level rigor in my personal curriculum—complete with departmental tracks across physical health, digital systems, personal identity, and cultural fluency. Structured like a university semester. Complete with readings, assignments, and tracking systems.

Multi-domain stimulation: I’m building Güld, a full-stack operating system for skilled labor, from the ground up—built for those who build everything else. I’m still stewarding Confess, a mezcal project built on slow growth and ethics. I’m co-creating Grooovee, a lifestyle beverage with real function and aesthetic discipline. I’m writing two novels. I’m designing systems, decks, brands, and operational infrastructure that function like case studies in strategy.

Creative and domestic fluency: I’m sewing clothes and soft goods—for our home, for my husband, for the joy of making beautiful, useful things. I’m knitting, crocheting, cooking, baking, homemaking—because those are expressions of order, intention, and love. They aren’t “nice to haves.” They are part of how I live, design, and restore.

Technical architecture: Rewriting how I use every tool. Automating my iPhone, structuring Apple Reminders, rebuilding my digital taxonomy in Notes, reconfiguring iCloud permissions, and cross-platform workflows. I’m not playing with tools. I’m eliminating friction.

Creative friction: Essay writing. Long-form systems thinking. Brand development. Everything is a testing ground for narrative intelligence, taste, and intellectual range.

Professional discernment: I’m applying only to roles that require my whole mind. That means upstream ownership, not downstream rescue. Strategic architecture, not ops patchwork. I’m calibrating for clarity, consequence, and scale.

This isn’t a hobbyist renaissance. This is a full-stack recalibration.

Every project, system, ritual, and constraint is part of a larger thesis: that my best work happens when I’m fully engaged—not just useful. That being impressive was only ever the opening act.

Now I want mastery. I want consequence. I want my mind stretched across real architecture.

Why I’m Done Being Impressive

Impressive was never the goal. It was the side effect of overdelivering in too many rooms at once.

Now, I want to move differently. With higher standards and deeper focus. With sharper thresholds and slower yeses. I’m not building a reputation. I’m building capacity.

Because the truth is, I’m not afraid of pressure. I’m afraid of stagnation disguised as success.

I want to work where good thinking is oxygen. Where systems are elegant, not duct-taped. Where the quality of the question is more important than the quantity of the answers.

Not because I think I’m better than the average operator. But because I’ve proven I’m excellent at being one. And now I want more.

I want to be necessary in a way that can’t be faked. I want to be essential to the architecture.

Not the name you call when something breaks. The name you trust to build it so it doesn’t.